Big fish: Iowa State faculty-student team creates immersive art experience in Johnston

08/02/21

AMES, Iowa — A leaping largemouth bass has landed in the new Johnston Town Center. Weighing 2 tons and measuring 20 feet long, 13 ½ feet high and 10 feet wide, the stainless steel sculpture shimmers with nearly 2,000 kinetic “scales” that capture the light and breeze to heighten the sense of movement created by the curving frame.

The “Ripples” (aka “Big Fish”) installation was designed by Reinaldo Correa Studio. Artist Reinaldo Correa, an Iowa State University assistant teaching professor of architecture and industrial design, and his team won a public art competition curated by Liz Lidgett Gallery and Design for the town center, a project by OPN Architects, Confluence, Hansen Company and Hansen Real Estate.

Beginning in February 2020, Correa — who has completed several public art commissions in Iowa — did research and interviews with community members to become better acquainted with Johnston and the surrounding area while developing a concept for the contest submission. For him, the project site’s proximity to Saylorville Lake and the city’s Terra Lake, both popular recreational destinations, emphasized the importance of water in connecting people with places through memories.

“Both bodies of water create ‘ripples’ of remembrance, from boating and fishing to picnics by the shore,” Correa said.

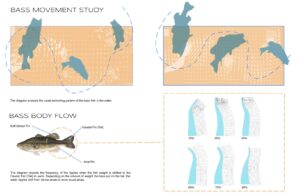

The largemouth bass is a common lake species that also causes distinctive ripples as it swims and slaps its tail fin while leaping to capture insects or bait. Correa chose the fish as a symbol to represent the value of the area’s aquatic recreational opportunities and their role in creating fond family memories.

Student collaboration

With many summer internships canceled because of COVID-19, Correa invited architecture students Brenna Fransen, Dai “Bill” Le and Tarun Bhatia, and industrial design students Joe Fentress and Ryan Fransen to collaborate with him through his studio practice on the Ripples proposal.

“I thought it would be a great opportunity for them despite the circumstances,” Correa said. “I’m always trying to bridge the gap between academia and the professional practice experience. If you empower students to be a part of the design process, they will bring so much to the table. This excites me as a teacher.”

The team followed university pandemic precautions and completed the project virtually as much as possible. Correa and students met over Webex and Zoom and used digital tools like Rhino, Grasshopper, SolidWorks, CAD, Google Docs and Miro to share files and feedback.

“In early versions of our proposal, the sculpture was enclosed and experienced entirely from the outside,” Correa said. “Then one of the students said ‘let’s open up the fish’ so people can see it from within. Through brainstorming and allowing all team members to have a voice, the project took a new direction and became better.”

Site integration and safety

Similarly successful collaboration with the professional design and construction firms engaged in the Johnston Town Center development led to greater integration of the Ripples artwork into the rest of the site, which consists of a plaza with a splash pad, ice rink and new state-of-the-art city hall with a large green lawn space.

“As a team, we began thinking of ways to integrate a secondary plaza area that would complement the artwork and extend the idea of a largemouth bass leaping from the water. Together with OPN Architects and Confluence, we designed a series of concentric ripples, made of stone and concrete, that create a visual relationship between the artwork and the ground,” Correa said.

“It not only adds to the textures of the artwork, it’s also a very practical thing — it alerts visitors that they’re getting closer to the installation while bringing attention to the in-ground recessed color-changing LED,” he said.

Safety and access were key considerations in developing the “Ripples” project. Part of Brenna Fransen’s role was to look at how visitors would interact with the artwork.

“Young children might be crawling, parents may have strollers and some people may use walkers or wheelchairs,” said Fransen, from Dubuque, now a fifth-year architecture student. “We placed the sculpture at an intersection for access without barriers.”

Seamless storytelling

Fentress, from St. Louis, who graduated with a bachelor of industrial design in May, assisted with designing the overall fish and different ways of attaching the scales to the sculpture scaffolding. He sought to tell a story with form, asking, “How do we implement form into the sculpture in a way that feels seamless and structured?” he said.

“I love straddling the art and design line, and I’m excited to see ‘Ripples’ exist in the real world.”

Le, from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, also now a fifth-year architecture student, spent much of the development phase assessing the unique movements of each fish scale. Using computational design software like Rhino and Grasshopper, the team created a 3D model of the sculpture and generated a point cloud form of the model, which allowed them to see different solutions for the size and shape of each component and the placement of each scale.

“When Reinaldo first approached me to participate, I felt as though I was out of my element. Something about public art and seeing a project from conception to reality drew me in, and this project gave me opportunities to make mistakes while learning from challenges,” Le said. “I’d never had a hands-on experience like this before, and I learned so much.”

Custom components

One key lesson the students learned: with such a complex piece, the team couldn’t rely on off-the-shelf materials.

“Sometimes what you’re looking for doesn’t exist. You can’t get it in a big-box store; you have to make it yourself,” Correa said. “This entire sculpture is an embodiment of that. Everything, from the frame to the screws to the clamps to hold the individual scales in place, is 100 percent custom.”

After learning that his studio had won the public art commission, Correa began working with local fabricators and manufacturing companies to produce the various components. The entire piece is stainless steel with multiple finishes. The ribs were sandblasted to create a “foggy” effect, while the scales have a combination of treatments that contribute to the rippling and shimmering effect.

A programmable LED lighting system will illuminate the interior “belly” of the fish with cooler tones and the exterior with warmer tones indicative of sunrise and sunset in Iowa.

“It’s like when you’re walking by a lake and see the reflection and refraction of light in the water — that’s the color palette we aimed for,” Correa said. “Lighting is a part of the spatial and visual experience.”

Grand opening

The 4,000-pound frame, inspired by wooden boat building, was craned into place the week of July 12, and scales were assembled and installed during the last week of July. The public is welcome to experience the artwork now; a ribbon-cutting ceremony will be at 4 p.m. Saturday, Aug. 28, during the Johnston Town Center’s grand opening event.

“A lot of credit goes to the city of Johnston. Many people think of art as an amenity, not a necessity, and sometimes communities don’t see value in these types of projects,” Correa said.

“The initial vision for this piece started small. Through conversations with residents, city officials and the public art committee, we recognized the potential to create something larger and more meaningful — a landmark attraction in Iowa where families can interact and make memories. ‘Ripples’ evolved to the scale and significance it has today because of the city’s willingness to expand the vision.”

Contacts

Reinaldo Correa-Diaz, Architecture, 787-559-9841, rcorrea@iastate.edu

Brenna Fransen, Architecture student, bfransen@iastate.edu

Bill Le, Architecture student, daitanle@iastate.edu

Heather Sauer, Design Communications, 515-294-9289, hsauer@iastate.edu

-30-